As Venice marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Marco Polo, one of the enduring mysteries is why he is absent from the meticulous Chinese records, which include mentions of far less illustrious visitors at a time when those included self-proclaimed ambassadors who tied a rag to a stick to pass it for the flag of non-existing countries, many of whom waited for years in overcrowded inns for an audience that, more often than not, would never come. While the Mandarins’ archives may suffered in any of the outbursts of violence in China, it is still surprising that the Chinese literature of the time makes no mention of such a traveller, explorer, and merchant who was allowed into the Forbidden City and claimed to have such a close friendship with emperors, a favour denied more than two centuries later to Jesuit missionary and fellow Italian Matteo Ricci, who never met with Emperor Wanli.

Yet for good or bad, hardly anybody contributed more than Marco Polo to installing the idea of China in the imagination of the Venetian and Western public of his era, and perhaps ours too. The China Marco Polo visited was still the undisputed superpower of the world, a country that boasted the compass, gunpowder, papermaking, and printing, the “Four Great Inventions.”

Is the China of Xi Jinping a comparable power? Comparing historical characters and eras is a moot exercise with inconclusive results, notwithstanding the now trite comment by Karl Marx of history repeating itself, “the first time as tragedy, the second as farce”. Yet history is the first and fundamental framework of reference to understanding our present at a time when people, and possibly not a few decision-makers too, are ambling through the convulsions that are shaking the world like clueless tourists visiting cities and ruins they know nothing about.

The government of Xi is making threatening noises about the recent election of William Lai Ching-te as president of Taiwan on a pro-independence ticket, defying the one-China policy that has been a constant since the 1949 revolution that brought the Communists to power in Beijing and the displaced forces of the Kuomintang of Chiang Kai-shek to set up a parallel state on the island of Formosa, the Taiwan of today.

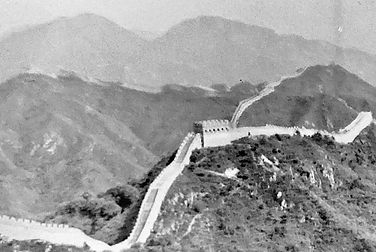

The comparisons of contemporary China to those of the Marco Polo era are tempting. More critically for world affairs too, China at the time had the largest fleet in the world, the sight of which (and if that was not enough, its firepower) moved the countries the shores of which were visited upon to become tributaries and pursue amicable relations with the invincible superpower. Much like the Great Wall, the Chinese fleet was the quintessential factor for the projection of power.

By the middle of the 15th century, however, warfare and the threats by the Mongols in the north, rebellions, and a reluctance by the rising Confucian bureaucracy to continue spending the vast sums required to keep the huge navy afloat, led to the dismantling of the treasure fleets of the legendary admiral Zheng He, who died in his seventh expedition in 1433. After that, China closed itself to the world. A centuries-long decline ensued, punctuated by the Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1860), the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the Rape of Nanking in 1937. Famines and disasters were also a recurring theme.

Now with the Communist Party firmly in control, unencumbered by war, unlike Russia, or the burdens of policing the world and its intractable conflicts, unlike the United States, and its material might fully restored—the second largest economy in the world by most measures, if not the first—China can turn its attention to what it sees as its inalienable historical right, which is returning Taiwan to its fold. Does this necessarily indicate the onset of an era of expansionism in China? Hardly. It has never renounced Taiwan as part of its country, much as the Russian aggression of Ukraine, regardless of the different keys according to which it can be read, is probably pan-Slavic in nature, as the Russian state and not few among the people never ceased to see Ukraine as one half of the same country. That this does not correspond to the feelings of a majority of the Taiwanese and possibly the totality of the Ukrainian people does not seem to bother Beijing or Moscow.

Yet unlike Russian rulers, who incur into boundless megalomaniac ambitions whether in the guise of Tsarist faux enlightenment, Soviet faux internationalism or Putin’s faux nationalism, the Chinese have always shown much more restraint. Even though fraught with unfathomable perils in the nuclear era, reuniting Taiwan to the Chinese motherland is not a benighted adventure. In 1975, in a conversation with then U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Chinese leader Mao Tse-tung (Zedong) showed no hurry in getting Taiwan back, because there was a “huge bunch of counter-revolutionaries there,” he said. “A hundred years hence we will want it, and we are going to fight for it.”

And what better example and metaphor than the Great Wall of China to illustrate the limits of its empire? They reputedly built it to keep the barbarians out, but even when they managed to get in, the Chinese eventually assimilated invaders into their civilisation, as they did with Mongols and Manchurians (but not with Marco Polo).